Mobile is not a neutral platform

For a decade or two, for most people 'the internet' meant a web browser, a mouse and a keyboard. There were a few things around the edges, like IM, Spotify, Skype or Steam (or, for some people, email), but for most people and for almost all activities, the web was the internet. The web was the platform, not the PC operating system - people created services for the web, far more than for Windows or MacOS.

And once the browser wars died down, the browser was pretty much a neutral platform. Browser technology changed and that made new things possible (Google Maps, say), but the browser makers were not king-makers and were not creating or enabling entirely new interaction models. The building blocks of the desktop internet in 1995 were pages and links and that was still the case in 2005 or indeed today. You might never actually see a URL and the pages might start blending into each other, but everything still happens in that framework.

On mobile this is different - it's the operating system itself that's the internet services platform, far more than the browser, and the platform is not neutral.

The first manifestation of this (but only the first) has been messaging. As I've written before, push notifications, home screen icons and easy access to address books and photos mean it's very easy to adopt a new messaging service and very easy to use several at once, where on the desktop web it would painful. It's not just that you're running an app instead of a web page, but that the app can leverage specific APIs on the platform that never existed on the web. The smartphone is itself a social messaging platform. Social apps plug into that platform rather like Facebook apps used to plug into the Facebook platform, or the way Facebook wants apps now to plug into Messenger.

All of those enabling layers and APIs are consciously controlled by the platform provider, and they keep changing things. We're post-Netscape and post-PageRank - we left behind a monolithic interaction model, the web, and a near-monolithic way to find things in web search, and now we have many models and no stabilisation around new ones. Apple and Google keep making decisions, enabling or disabling options and capabilities and creating or removing opportunities. This was also true of Windows or Mac for Windows or Mac applications (as competitors to Office complained) but in practice it wasn't the case on the desktop internet, because most of what mattered was happening inside the browser and not touching the OS, and the browsers themselves weren't making these kinds of moves.

The crucial change is that Netscape or Internet Explorer did not shape which websites you visited (though toolbars tried to) and they didn't do things that changed how user acquisition or retention worked online. Apple and Google do that all the time, both consciously and unconsciously - it's inherent in what an actual operating system means. Some of this is simple evolution, and often collaborative - the emergence of deep links is a good example of this. But some of it isn't.

Hence, at both IO and WWDC this summer we saw moves from Apple and Google to create their own real-estate around the home screen. The 'swipe left from home' screen gains more and more capabilities, all totally under the platform owner's control. A lot of this happens to be about attempts at basic 'AI' - to watch the user in different ways and suggest something useful - but the broader point is that this is Apple's screen or Google's screen, and another content provider gets there only if Apple or Google want (and if they implement the indexing APIs that Apple and Google require). This will get bigger.

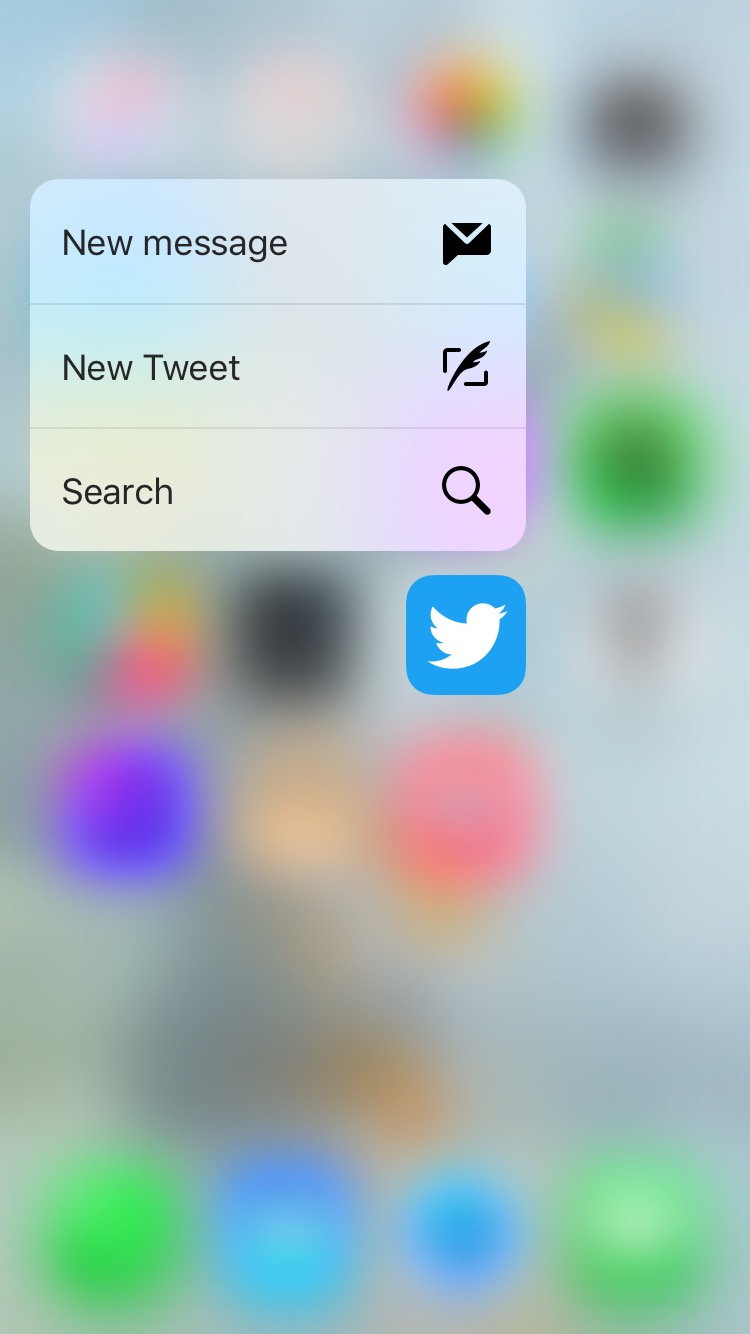

Next, Apple and Google are exploring new ways to unbundle the content within apps into new usage models. Hence Apple's 3D Touch unbundles app content into the home screen (shades of Windows Phone) with these dynamic menus. Can there be apps where this is the main UI? Can you use them for notifications? (And of course this isn't on Android, so the fantasy of a cross-platform app gets even further away.)

Equally, Google's Now on Tap unbundles apps (and anything else) into Google's own search and suggestions. There's a nice dilemma here - when you implement the APIs to support app indexing and deep linking, you also let Google route people away from your app at a moment's notice (here a flow away from Soundcloud to YouTube, by pure co-incidence).

Of course, all this sort of stuff is a big reason why Google bought Android in the first place - Google was afraid that Microsoft (it was that long ago) would dominate mobile operating systems and shut it out. The obvious fear was around things like preloads, and the justice of that fear was proven right with Maps, where Apple Maps now has 2-3x more users on iOS than does Google Maps, despite being a weaker product - the 'good enough' default wins and the platform owner chooses what that is. But the deeper issue is that we haven't just unbundled search from the web into apps - we're now unbundling apps, search and discovery into the OS itself. Google of course has always put a web search box on the Android home screen (and indeed one could ask why there needs to be an actual browser icon as well) but this is much more fundamental.

That is, this isn't really about what kinds of boxes slide onto your screen from where. It's about how you talk to your friends, how you discover new services and how you decide to spend money.

This, obviously, is why Facebook keeps trying to insert its own layers into the OS (and why Amazon made a phone). I sometimes feel that every spring Facebook holds F8 and says "this is what interaction on smartphones will look like"!", and a few weeks later Apple and Google say "look, sorry kid, but...". It's not Facebook's platform to change. But if Facebook is successful in using Messenger to close the loop between its online identity platform (which both Apple and Google lack) and notification and engagement on the phone, then it it'll have managed to create its own layer at last.

Really, what we see here is a search for another run-time. We had the web, and then we added apps, and now we look for another. Notifications? Siri/Now? Messaging (as forWeChat in China)? Something else? But each of the previous run-times lacked search, discovery and acquisition as a fundamental part of the architecture - they had to be added later (and arguably that's still not there with apps). On Facebook's desktop platform, in contrast, both halves were there almost from the beginning. The next run-times on mobile might have both halves too.