Price

From 2007 to 2012 annual mobile handset sales grew from 1.1bn units to 1.7bn units. This was, obviously enough, driven by an expansion in the number of ‘human’ mobile phone users from 2.1bn to 3.2bn (the number of total connections was much higher).

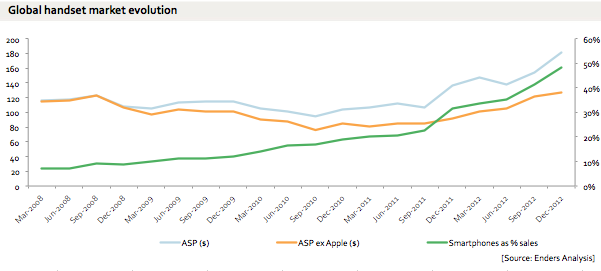

Almost all of the growth in subscribers and hence in handset volume growth came from the low end at low prices. So, one would have expected the average price of a phone to fall. It didn't.

ASPs (average selling prices) did indeed fall for a while, bottoming out in late 2010, but since then they've almost doubled, to a little over $180 per phone at the end of 2012.

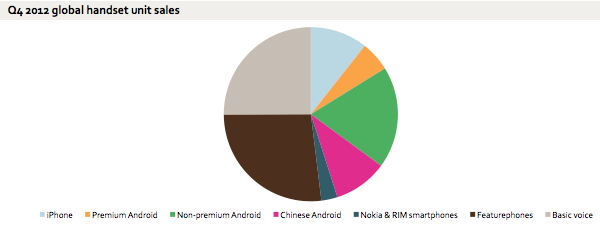

The reason for this, of course, is the arrival of smartphones, which have persuaded people to pay more for a phone than they ever did before. The iPhone, most obviously, sells in a super-premium $600+ bracket that barely existed before, and parts of the Android market (and to some extent Nokia) have followed. At the end of 2012, top-end smartphones amounted to about 17% of total phone volumes, and about half the revenue. Meanwhile a quarter of phones sold were still plain old basic voice phones.

The interesting question, to me, is what the third and fourth smartphone bought by a given person will cost. When do people decide that a $150 smartphone is good enough that it's an acceptable replacement for a two-year-old smartphone that cost $300 new? Or, do they decide to upgrade - to buy an iPhone 6 or Samsung GS5? Or do they just wait - buy a phone every three years instead of every two?

Moore's Law is working away on phones, and a $150 phone is indeed as good as a $300-$400 phone from two years ago - but the new $300 phone is also a dramatic improvement. The perceptible improvement of new product categories follows a curve over time: 20 years ago a new PC was noticeably better than a 2 year old PC, but today the gap with even a 5 year old PC can be pretty hard to spot. Hence, the PC replacement cycle has lengthened to 5 years, and average selling prices have steadily fallen. Phones today are at the steep part of the curve: there are still compelling reasons to spend the extra money, and to upgrade relatively frequently (and of course a phone gets scuffed and scratched).

Also skewing the purchase decision, of course, is subsidy: a $150 saving is only the price of a coffee and pastry each month over a 24m contract. This applies especially in the USA, where even a $400+ iPhone 4 costs the same to consumers as a $150 Android - both phones are 'free' and there's no difference in the contact price based on which you choose.

My suspicion is that we'll see a polarisation in the market. There is a portion of the market that will pay a premium price for the best phone possible - and for these people $600 (however manifested) is not actually that much money every two years. But the $300 segment may well get squeezed, between people trading up, paying the price of a coffee and croissant and getting an iPhone, and people trading down to a perfectly good $150 phone.

It is also, of course, entirely possible that the phone they trade down to is a $200 iPhone, a $150 Google 'Chrome' phone or a $100 Kindle Fire phone. At that point everything changes again.