Resetting online commerce

“Aunt Agatha's demeanour now was rather like that of one who, picking daisies on the railway, has just caught the down express in the small of the back.” - P.G. Wodehouse

I’ve spent a lot of time in the last few years looking at ecommerce and discovery - how do people decide what to buy online, when a shop can’t show it to them? It seems to me that pretty much every part of that question is being reset this year. There are half a dozen huge industries where all of the cards are being thrown up in the air, and no-one really knows where they’re going to land. The Covid lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 are catalysing and accelerating all sorts of changes - we’re getting five years of adoption in a few quarters, and five years of inevitability in the back of the neck.

Physical retail itself has been a ‘boiling frog’ for 20 years. Every year ecommerce gets a little bigger and the problem gets a little worse, but the growth in any given year was never big enough for people to panic, and you could always tell yourself that sure, people would buy that other industry’s product online, but not yours. I think we all now understand that anyone will buy anything online, given the right experience, and if your retail model is based on being an end-point to a logistics chain then you have an existential problem.

This is accelerated by lockdowns, partly because growth in ecommerce penetration that we all expected has been pulled forward, and partly because everyone is now forced to try buying things online that they might not have considered before (most obviously groceries, where UK online penetration has doubled from 5% of sales to 10% this year).

But the reduction in footfall itself also has cascading consequences. It’s pretty obvious that many US malls are anchored by large retailers that could very easily now go out of business, and then the other retailers in that mall that might have thought they were OK now aren’t - and then the mall itself goes as well. That purchasing won’t automatically go to those retailers’ websites, and it might also go to entirely different categories. If you change the channel then you change what gets bought.

A further and perhaps more interesting question is that a shift to working remotely might be a permanent change for many retail areas in big cities. Even if people now work from home only one day a week, how many retailers will experience that as a 20% decline in footfall, and how many cannot survive that? In some areas that might also be a vicious circle: more people working from home means less retail, and less retail in Canary Wharf or Hudson Yards might mean more people working from home. I’ve seen people call this a ‘donut’ effect - office districts of a city are hollowed out.

Then, what gets sold in those shops? In the last couple of years there’s been an explosion and arguable a bubble in so-called direct to consumer or ‘D2C’ brands. The bubble burst at the beginning of this year (ironically just before everyone had to buy everything online), partly prompted by the realisation that if you’re not renting a store on Fifth Avenue, that money doesn’t go to the bottom line - you’ll almost certainly have to spend it on delivery, advertising, Amazon placement or returns instead (in other words, there are no free lunches). But the reasons why that explosion had happened remain: you can now make and sell a consumer product without the same kind of fixed cost and upfront capital investment in a national retail footprint, inventory and marketing that would have been necessary 20 years ago. But what does that mean? What is a sustainable customer acquisition model? For how many brands, and what aggregation and discovery models? Is there any role for ‘software’ or is this really entirely a CPG and marketing story? And at what point do you need to get bought by P&G, or LVMH, or partner with Sephora, in much the way that you would have in 2000? (One part of the question - do these kinds of companies produce venture returns?)

I'm a terrified dinosaur” - Jorge Paulo Lemann, co-founder of 3G Capital, recent purchaser of Kraft Heinz

Those traditional brand owners are also scrambling. Many of the big consumer brands we all know have historically been B2B businesses. P&G doesn’t sell soap - it sells pallets of soap. Now all of these companies are trying to work out what a customer relationship would be, and how many companies can have that (hence, for example, Lululemon buying Mirror for $500m earlier this year). What does it mean to be a brand, or a brand owner, or for manufacturing, distribution and capital for those brands, when all of that is being unbundled and rebundled?

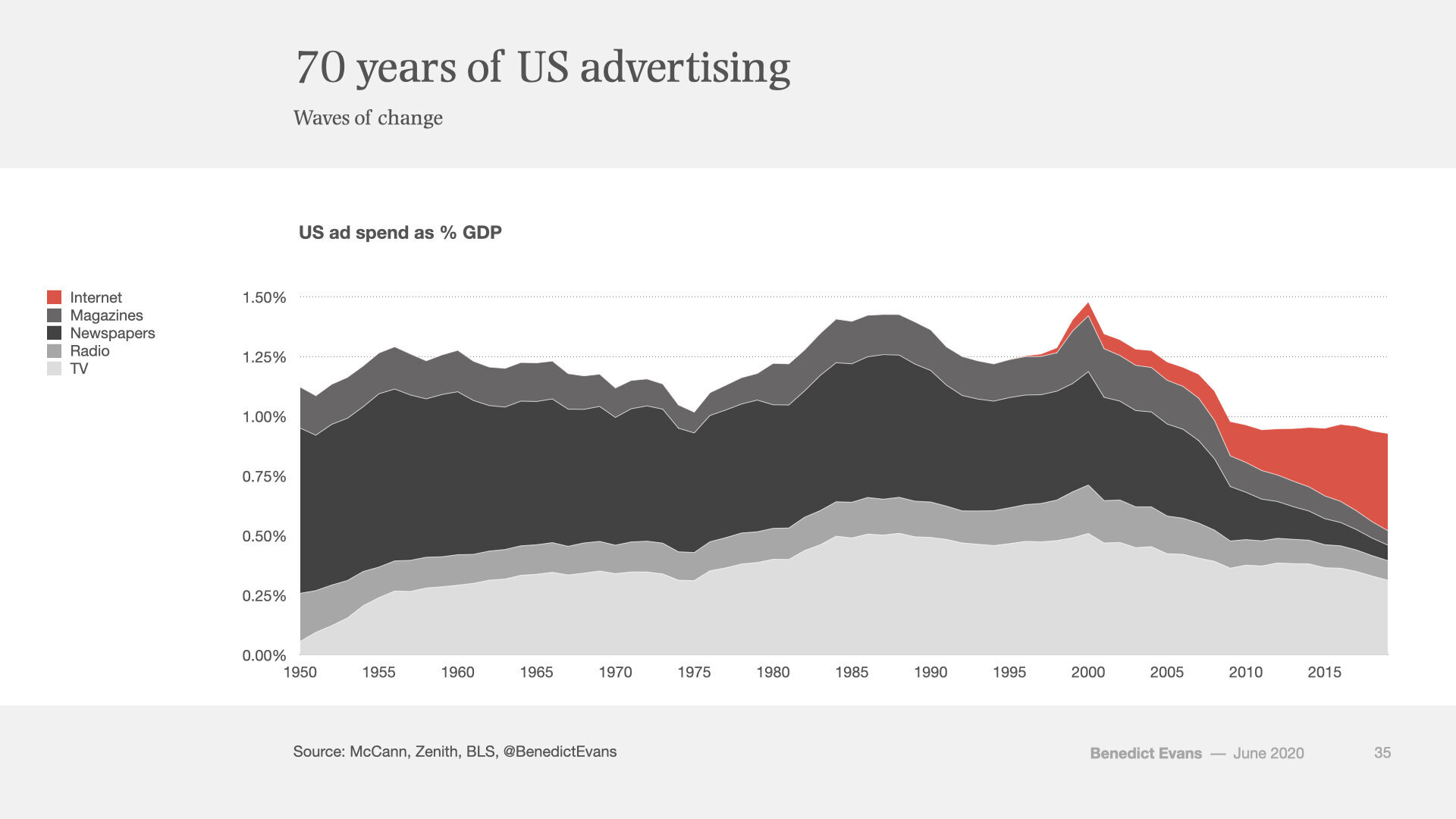

Meanwhile, if you’re now spending your acquisition budget on advertising instead of rent, what does that advertising look like? Again, no-one quite knows. Print advertising has collapsed. TV has been pretty resilient as the internet has grown (though the chart above suggests that its share of GDP has fallen significantly), but subscriptions and audiences are now decisively switching away from the old model, so what will that look like in 5 years?

And then there’s internet advertising, and that looks more uncertain than almost anything else I’ve written about here. Over the past 25 years, a huge inverted pyramid has been built up on top of cookies, much of which can often look more like rent-seeking, arbitrage and general spivery than rational economic optimisation. Earlier this year PwC carried out a study of UK online advertising suggesting that not only does half of ad spending not actually make it to publishers, but that 15% couldn’t be traced at all.

Source: PwC for ISBA

Today, privacy changes by Google and Apple on one side (in Chrome, Safari and iOS), and GDPR, CCPA and a whole bunch of other blunderbuss regulation on the other, are shoving over that whole tottering mess of tracking, targeting, interest and identity management. I’ve sometimes had the impression that almost no-one in Silicon Valley that doesn’t actually work on an ad team really pays any attention to ‘ad tech’, but now that whole business is being reset.

Quite separately, Google and Facebook’s own ad market position (they have at least half of all online advertising) is attracting very serious scrutiny from competition regulators, especially in the UK and EU, with all sorts of suggestions of highly technical and specific intervention into the mechanics of their market dominance - many of which incidentally are in direct conflict with what the privacy regulator next door is demanding. The competition regulator says ‘make it easy to move data around’ and the privacy regulator says ‘don’t’.

Online advertising is now worth perhaps $250bn, but advertising in total is $500bn and all global marketing is closer to $1tr. Telling people about things they might like or be interested in has value, and it isn’t actually evil a priori, but if you can’t ‘track’ people across the web anymore, how do you do that? And how do you reconcile that with wanting more competition to Google or Amazon? I hope that the answer is not that the only companies that can do interest-based ads are Google and Facebook on one hand and brands with their own huge audiences and data such as the Guardian or New York Times on the other. Will one or other of the various industry data initiatives work? Will Apple try a generalised identity or interest platform? I don’t know, but I do know that a trillion dollar industry is up in the air.

I don’t know the answer to most of these question - more importantly, I don’t really know the questions. What will happen in TV? I don’t know - ask a TV analyst! What will happen to all these D2C CPG companies? I don’t know - ask a CPG analyst! But of course, they don’t know either.