COVID and forced experiments

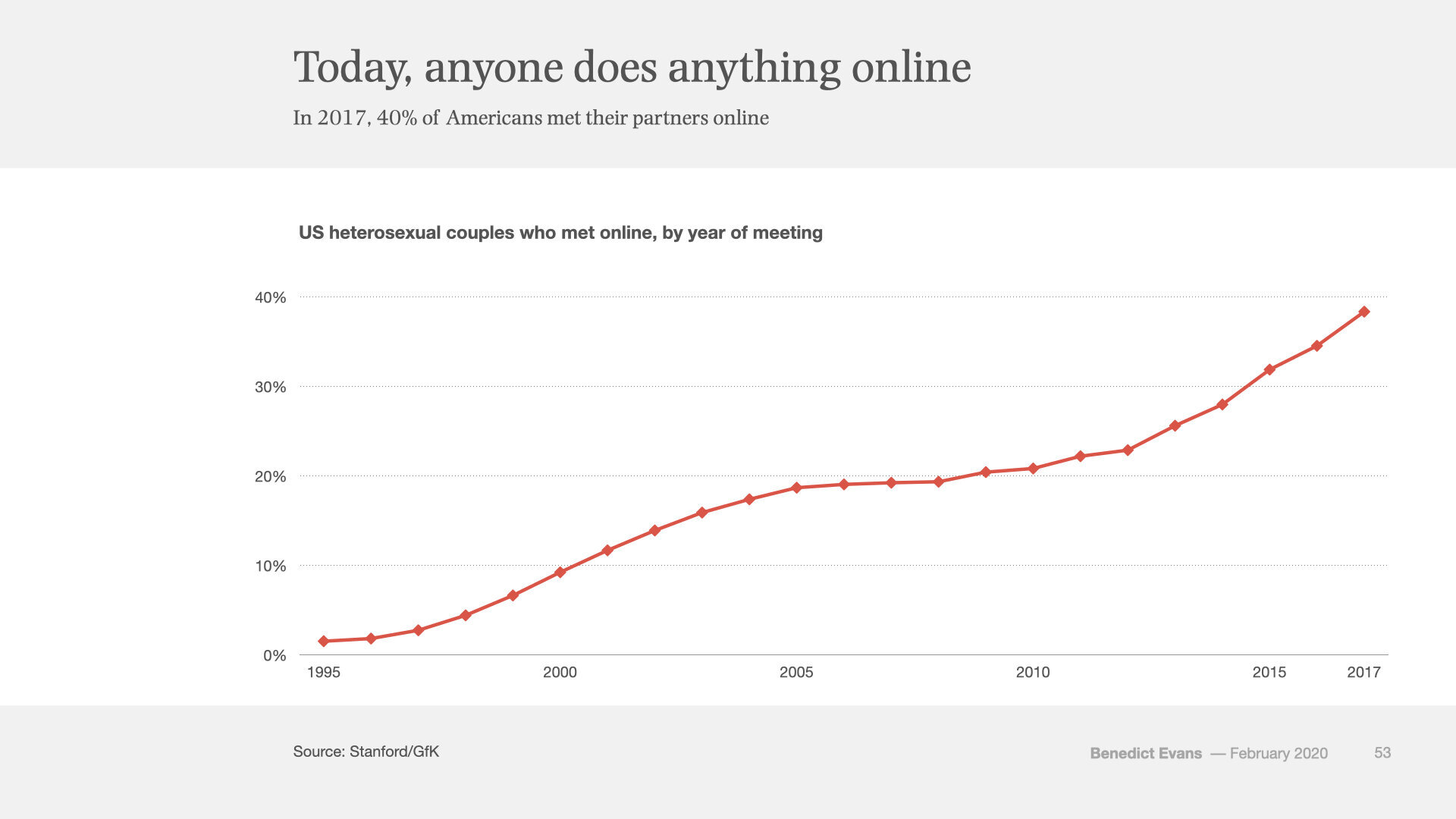

At the beginning of this year (which now feels like 100 years ago), I gave a presentation on macro trends in tech, at an event in Davos. There were lots of charts, but I think this one matters most. In 2017, 40% of new relationships in the USA began in a smartphone app. By 2019 that was probably closer to 50%.

For the last 20 years, people have looked at new digital devices, services and behaviours and said ‘yes, but most people…’ Most people aren’t online; most people don’t have broadband; most people don’t have 3G; most people don’t have a smartphone. After all, when Netscape launched in 1994 there were less than 50m consumer PCs on the whole planet.

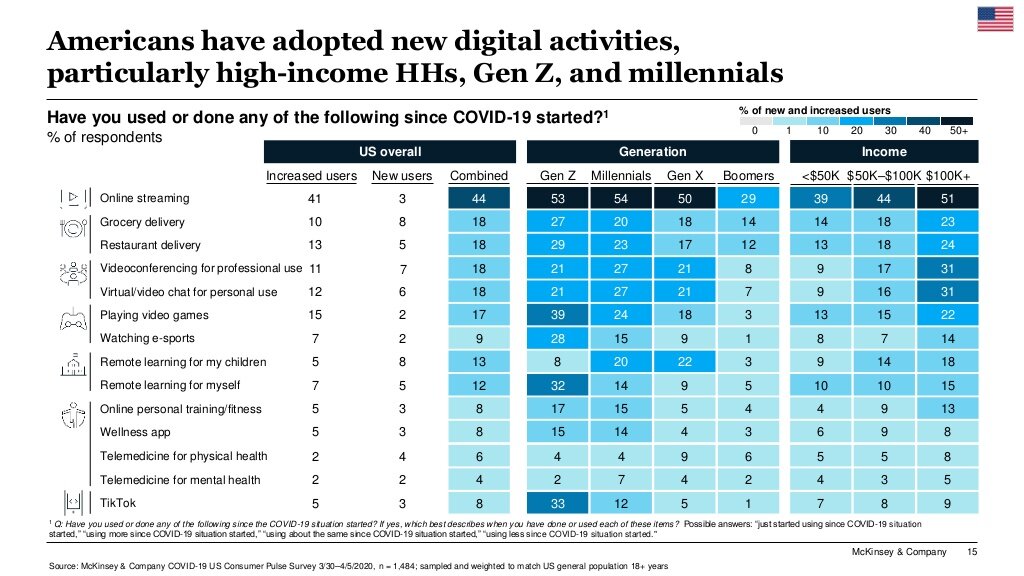

But today, over 4bn people have a smartphone - 75% of the earth’s adult population. Over 80% of American teenagers have an iPhone. That still isn’t literally everyone, but the default assumption has reversed. We’re all online now, and, just as importantly, we’re all willing to use this for any part of our lives, if you can work out the right experience and business model. Today, anyone will do anything online.

This isn’t the same as saying that everyone will do everything online. You might compare ‘online’ to cars - not everyone has a car, and no-one does everything with a car, but there is no part of the population and no activity or part of life or the economy where cars do not apply.

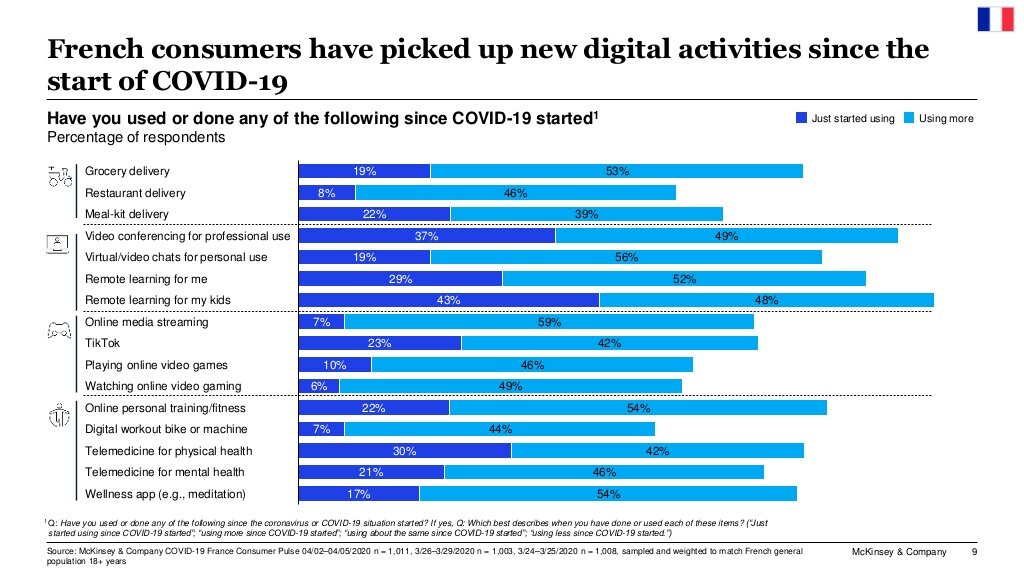

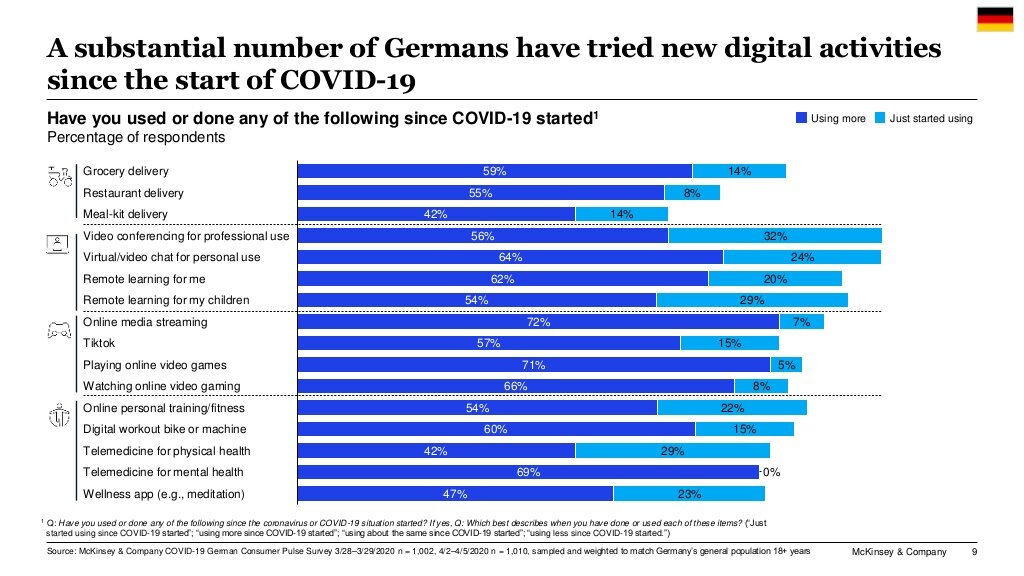

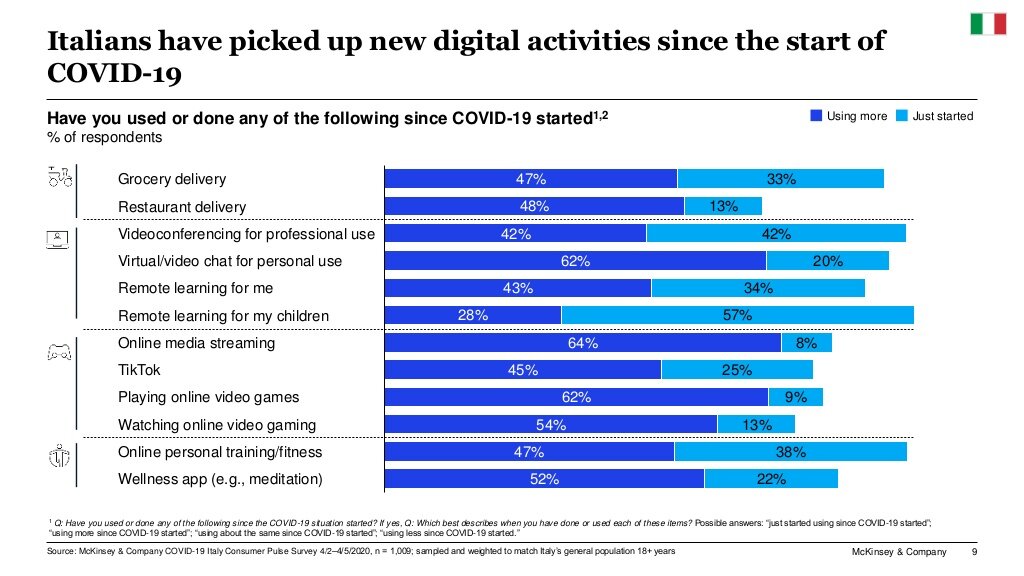

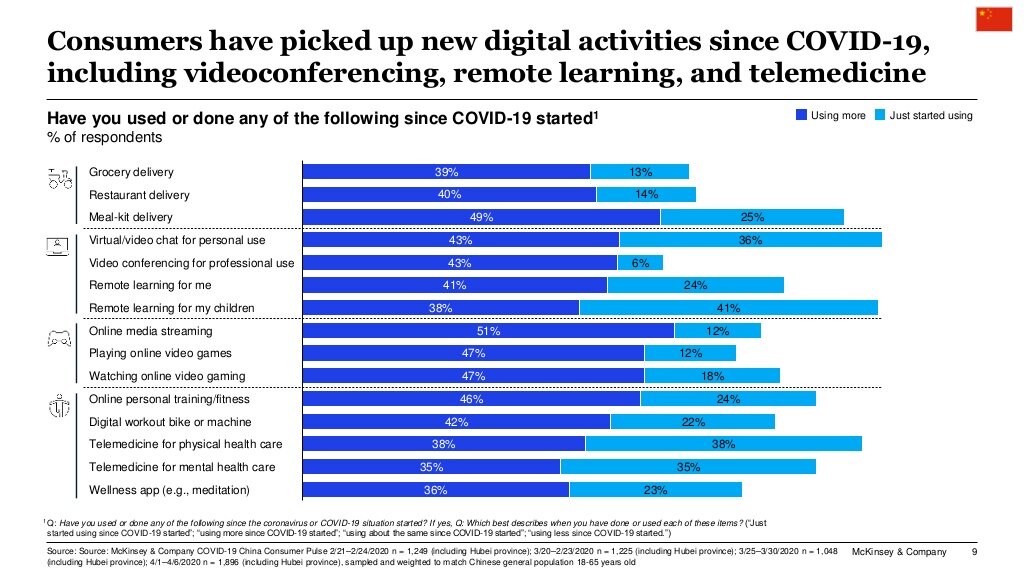

That was January, but now most of us are shut up inside for weeks and quite probably longer, so (besides other more important things) we wonder how this might be accelerated. Everyone is now being forced to do almost everything online, or at least try to, so what will change? Some things were very clearly already happening and will now happen faster, possibly much faster, and some things that we’re forced to try now might not have happened without this. But, not all of this adoption will stick once we do get back to normal. We’ll try everything, because we’re forced to, but not all of it will work. So, which is which?

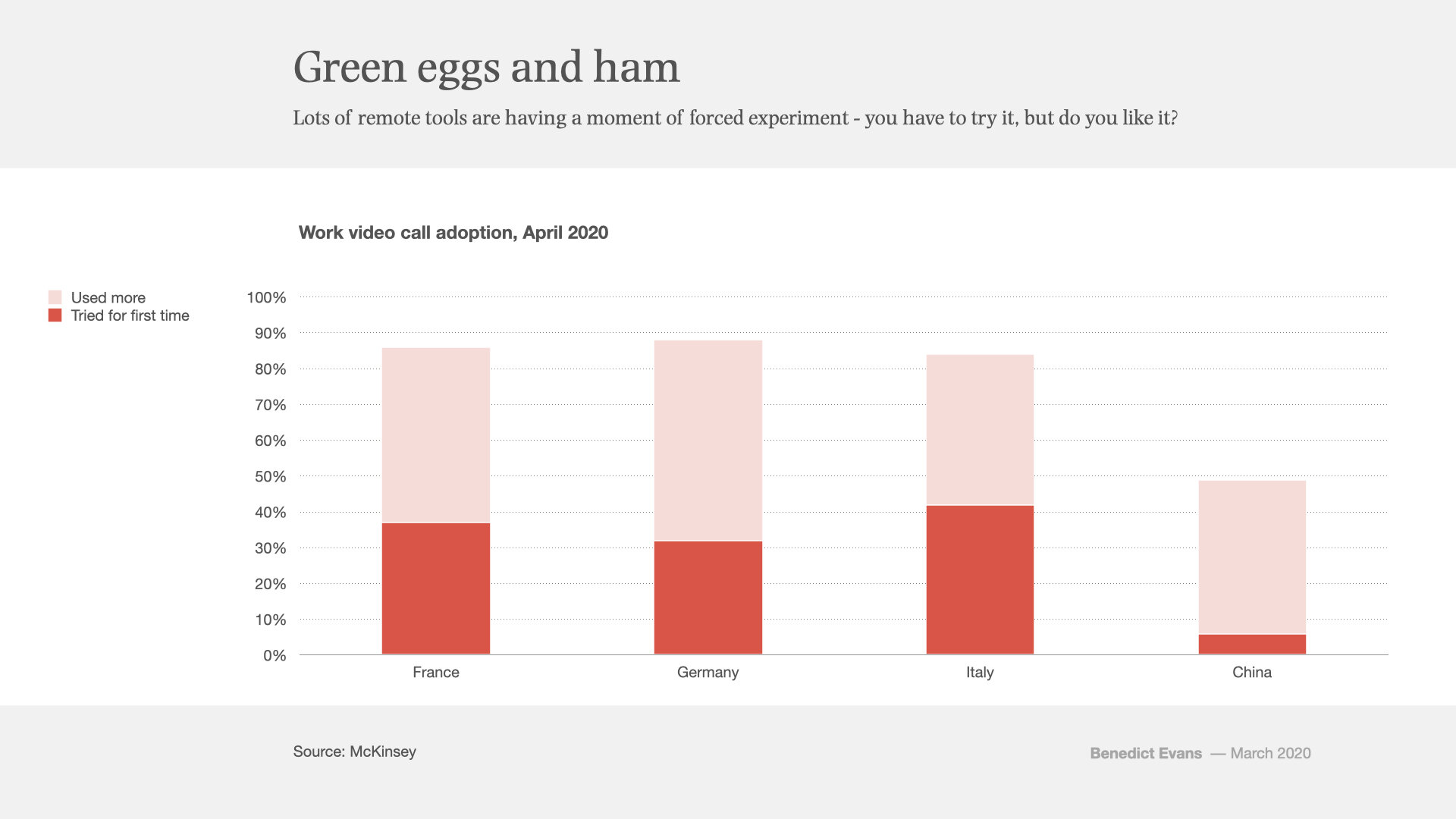

Most obviously, people have been talking about remote work and video calls for decades, but now a huge number of ‘quick coffees’ and ‘team stand-ups’ have been displaced onto video almost overnight. Zoom has gone from 10m to 200m daily users, and Zoom, Google Meet and Microsoft Teams combined probably now have more call volume than the entire US mobile network*. How much of that will go back to cafés and meeting rooms? And are you really ‘just as productive’ at home?

Well, it depends what you’re trying to do. if the job is ‘forming a human connection’ or ‘empathy’, then a video call might not be the right approach, and we may go back to coffee. If the job is to exchange information or update a project status, then video might be fine. But you could also ask whether it needs to be a call either - is that really the job you’re trying to do? Sometimes an in-person meeting is a human connection and video might or might not convey that well, but sometimes video is skeuomorphism and both calls and meetings are a way to use unstructured data to transmit structure. So, should the meeting go to a call, or should it go from synchronous to asynchronous (i.e. Slack, Teams, or even email), or should it go to some more structured data form? How many processes in how many industries convert from in-person meetings and phone calls to Zoom, and how many convert to something like Rigup or Honor, or Figma or Frame.io - to tools, structure and workflow? How much clerical work gets automated into structure, and how much time does that create for those in-person meetings where the actual in-person meeting is the point?

Every time we get a new kind of tool, we start by making the new thing fit the existing ways that we work, but then, over time, we change the work to fit the new tool. You’re used to making your metrics dashboard in PowerPoint, and then the cloud comes along and you can make it in Google Docs and everyone always has the latest version. But one day, you realise that the dashboard could be generated automatically and be a live webpage, and no-one needs to make those slides at all. Today, sometimes doing the meeting as a video call is a poor substitute for human interaction, but sometimes it’s like putting the slides in the cloud.

I don’t think we can know which is which right now, but we’re going through a vast, forced public experiment to find out which bits of human psychology will align with which kinds of tool, just as we did with SMS, email or indeed phone calls in previous generations. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of software engineers are cooped up at home getting frustrated with their current tools and wondering if they can spot some pain point, or mechanic, or small difference to the flow, and solve some opportunity that no-one ever quite realised was there. Those insights let Zoom carve out 200m users in a space where all of the incumbent tech giants thought they had established, mature products. In that, Zoom reminds me a lot of Dropbox - everyone told Drew Houston ‘there are dozens of these already’ and he kept replying ‘yes, but which ones do you use?’ A lot of companies will be born in nine months, and more of them will be the next Slack or Dropbox than the next Zoom.

Much the same kinds of questions apply to ecommerce. Again, we’re having a massive forced experiment and we ask what will stick, and again, some of the answer lies in what ‘job’ you were really trying to do. Instead of asking ‘ did that have to be a physical meeting?’ we ask ‘did you have to go to a physical shop?’ That’s a conversation we’ve been having for 20 years - some parts of physical retail are mostly logistics, convert fairly easily to online, and the questions are mostly about unit economics (especially for groceries, which need a whole new logistics chain), and other parts are more about service, recommendation and discovery, are harder to convert, and produce different kinds of innovation. The most interesting parts of last year’s D2C bubble were about experience, not logistics, and it’s ironic that the bubble popped just as COVID started to spread.

Today, though, there are two new parts to that conversation. First, this period of forced experimentation means that people have to at least try experiences such as grocery delivery that they would often have dismissed before - there’s a ‘Green Eggs and Ham’ moment. But second, some physical retail just won’t be there anymore when we go back outside, and some of the demand that has disappeared for the moment won’t come back either. Some retail will go out of business, and that purchasing won’t necessarily go to other physical retailers - there may be no physical option at all anymore, and either way it may go online, but it also may just go away, and the money be spent on something else entirely. Our assumptions of how we buy but also what we buy are being reset.

Even as some companies, sadly, will go out of business, the present surge in demand for online is also creating opportunities for companies in both software and ecommerce. In ‘normal’, steady state growth, the default choices and the incumbent companies soak up most of the new use, unless you carve out some radically new market (such as Warby Parker). But when the incumbents are swamped and everyone is frantically trying everything, it may be easier for new voices to be heard. Again - the market is being reset.

You can see that market reset in another way in two big industries that people have spent decades dreaming of moving to digital and to remote - health and education. Both of these are very obviously now in the same period of forced, accelerated adoption and experimentation, but they are also short-circuiting many of the barriers to adoption and experimentation that have made both industries graveyards for innovation and company creation for a decade or two.

In the past, the problem with both of these markets was that you had to solve the product and user adoption challenges that also apply to productivity, ecommerce or anything else, but then you also had to solve a route to market characterised by multi-year sales cycles and long-term locked-in contracts, a highly bureaucratic customer, complex regulation (often necessarily, which tech people sometimes forget), and complete separation between the purchasers (who care about price and a list of features) and the users (who care about usability and efficiency). All of that meant that creating great tools often turned out to be easier than making a sale and building a business. So, when the irresistible force of lockdown and remote work collides with the immovable object of all the prior barriers to adoption, what happens? In the past few weeks we’ve see adoption in days or weeks that would previously have taken months or years - this NY Times story is a good summary of that for healthcare in the UK. Again, not all of this will stick, sometimes the doctor really does need to be in the same room, and some things will come back. But this time, we also ask whether and which of the external, bureaucratic barriers to adoption and creation will come back, which can be left behind and which really were necessary.

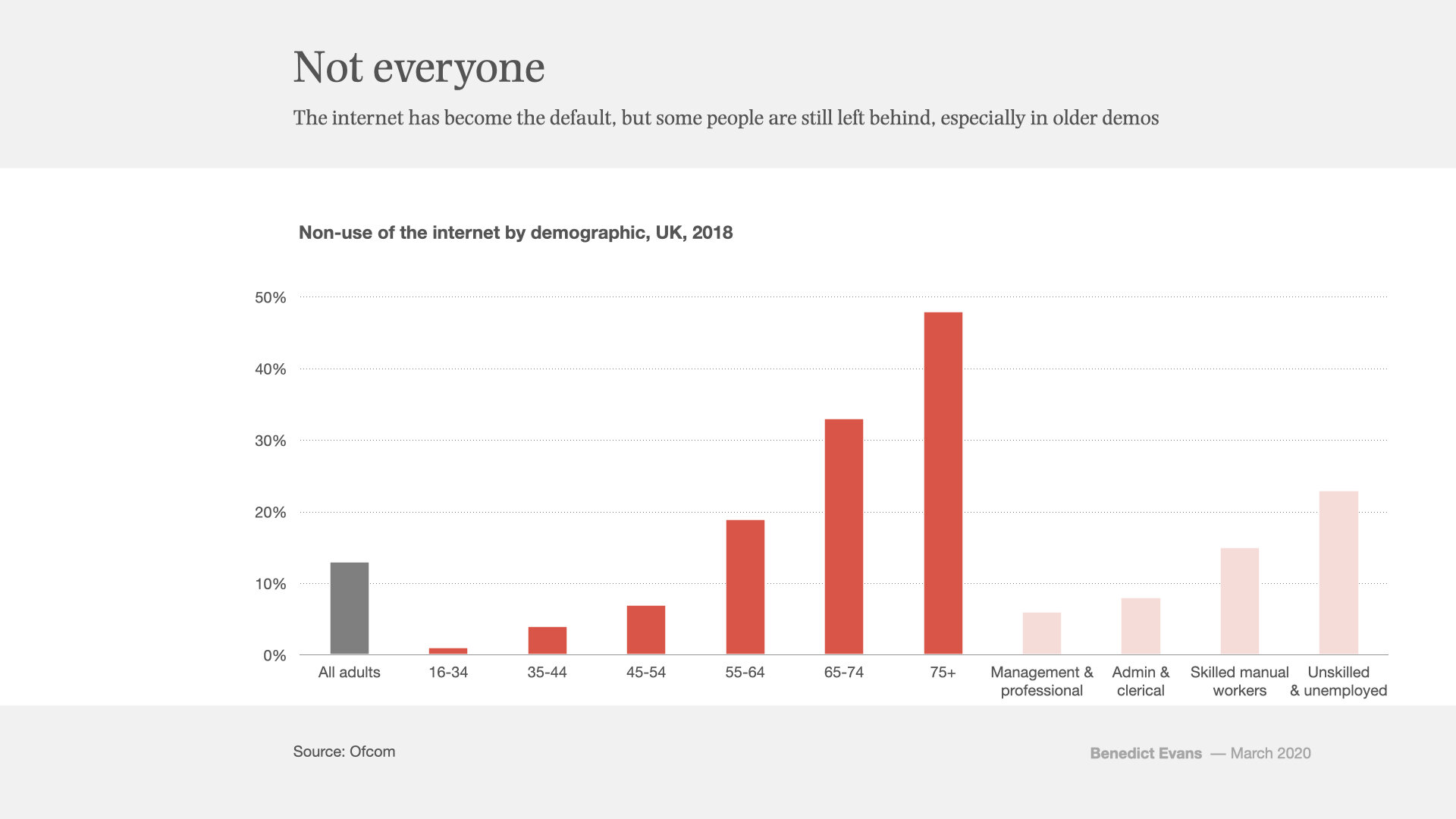

Finally, there’s another kind of ‘left behind’ to think about - though the vast majority of us are now online, there are still tens of millions of people in the developed world who are not, mostly (they say) because they don’t see the point. As the UK data below shows, this tends to skew to older people, and to a lesser extent to lower incomes. This has become particularly relevant now that the old are encouraged to use online grocery delivery. What seems both easy and obvious to you may not to your parents, ‘forced adoption’ or not.

Moreover, even amongst the people who are online, not everyone is especially comfortable. I’ve always remembered this anecdote, from another Ofcom study.

The internet and smartphones have become the default presumptions - ‘everyone’ is online, and software ate the world, and that creates and created industries. But you do have to remember the people who aren’t online, when the library’s shut and the smartphone screen is cracked.

* Microsoft had a peak of 2.7bn daily minutes and Google has ‘over 2bn’. Zoom said it was at an annual run-rate of 100bn in January (2-300m daily), but the user base is up 10-20x since then. Total US mobile phone traffic is about 6.5bn daily minutes.