Retail, rent and things that don’t scale

Morioka Shoten

I generally think about retail as sitting on a spectrum from logistics to experience. At the logistics end, you know exactly what you want and retail’s job is to provide the most efficient way to get it. At the experience end, you don’t know, and retail’s job is to help you, with ideas, suggestion, curation and service.

Ecommerce began at the logistics end, as a new and (sometimes) more efficient way to get something. It’s not always more efficient - you don’t have your lunch mailed to your desk. Rather, the right logistics in retail is a matter of algebra. How much inventory is needed, how many SKUs, how big are the products, how fast can they be shipped, how often do you buy them, how far would you be willing to drive or walk, does the product need to be kept cold, or warm, what’s the cost per square foot - there are all sorts of possible inputs to the equation, and if you visualised them all you’d have a many-dimensional scatter diagram, that would tell you why Ikea has giant stores on the edge of town, why Walgreens has small local stores, and why you can buy milk on every block in Manhattan but not a fridge.

The internet adds a new set of possibilities to that algebra. Amazon sells anything that can be stored on a shelf in a vast warehouse and shipped in a cardboard box. It doesn’t so much have ‘infinite shelf-space’ as one shelf that’s infinitely long: it only sells things that can fit into that model. Grocery delivery is an entirely different model, that needs quite different storage and quite different logistics; so in turn is restaurant delivery (or take-away, which is at least a third of US restaurant spending). Meanwhile, the online mattress business was founded on the flash of insight that if you vacuum-pack a foam mattress then you can ship it like any other parcel, and bypass the existing mattress industry’s distribution model, but that also means you can’t do returns. Mattresses, books and sushi can all be bought ‘online’, but those are as different from each other as Walgreens and Ikea. They’re all algebra - all different points in that scatter diagram - and a binary split between ‘online’ and ‘physical’ retail is less and less useful.

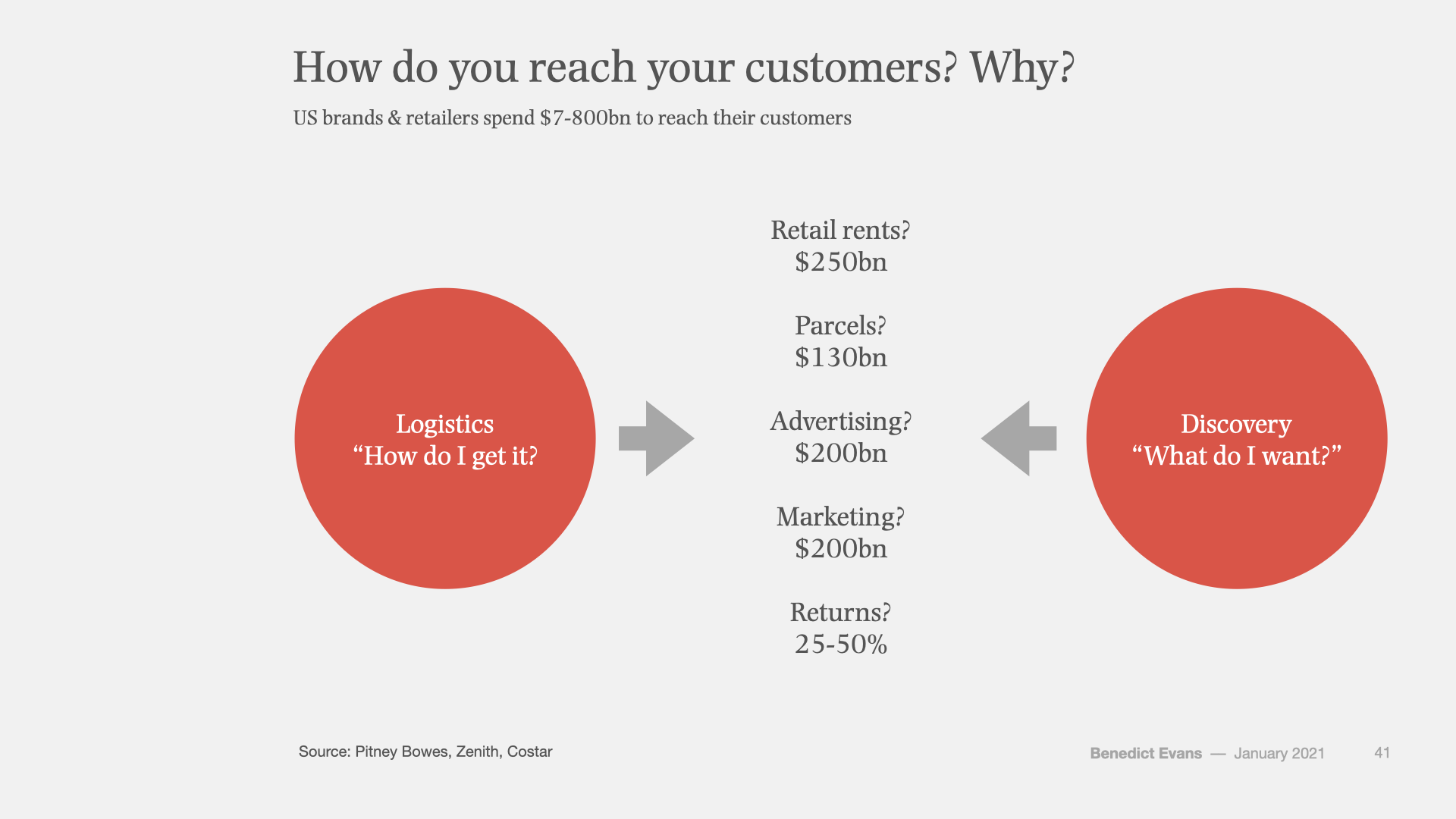

Part of that algebra is that all sorts of things that were previously separate budgets become part of the same question. Should you spend your acquisition budget on search ads or free shipping? Or a better returns policy? If you open a store in that city, can you spend less on Instagram, and do your returns go down or up? How do you reach your customers, and who are they? There’s long been a joke in D2C that ‘rent is the new customer acquisition cost’, but what is an Amazon truck?

The further any retail category gets from these logistics questions, the less well the internet has tended to work. It’s much easier to connect a database to a web page than to put human experience on a web page. The Internet lets you live in Wisconsin and buy anything you could buy in New York, but it doesn’t let you shop the way you could shop in New York. And so a lot of the story of ecommerce in the last 25 years has been on one hand converting things that looked like they needed experience into logistics but on the other hand trying to work out how to build experience online. People will happily buy books without seeing them, and they will buy shoes if you add free returns (turning experience into logistics), and they will also buy high fashion or $100,000 watches but, now, you will need to solve experience, because that’s really what matters, not just the logistics.

Part of the promise of the internet is that you can take things that only worked in big cities and scale them everywhere. In the off-line world, you could never take that unique store in London or Milan and scale it nationally or globally - you couldn’t get the staff, and there wasn’t the density of the right kind of customer (and that’s setting aside the problem that scaling it might make people less interested anyway). But as the saying goes, ‘the internet is the densest city on earth’, so theoretically, any kind of ‘unscalable’ market should be able to find a place on the internet. Everyone can find their tribe.

This sits behind some of the explosive growth of Shopify, which handled over $100bn of GMV in 2020, and behind Instagram, and the influencer thing, and subscriptions, and now live video and AR. How do you take that experience from 1,000 square feet in Soho or Ginza to a screen? Of course, some of what Instagram and influencers are doing is unbundling magazines, and magazines are also a way to take the big city experience to everyone. But I wonder now how much more you can pick up those spikes of weird, quirky, interesting things in a few cities and take them everywhere.

I described retail as logistics and experience, but it’s also culture. What will happen as the generations that grew up with ecommerce no longer see it as new and exciting but instead internalise it, and take ownership? Retail is pop culture, and that’s live streaming but it’s also the shop that only you know about. Maybe the internet is due for a wave of things that don’t scale at all. In that light, I’ve been fascinated by ‘Morioka Shoten’ in Tokyo - a bookshop that sells only one book at a time. This is retail as anti-logistics - as a reaction against the firehose, and the infinite replication of Amazon. Before the internet that would only work in a very dense city, but, again, the internet is the densest city on earth, so how far do we scale the unscalable?