Boxes, trucks and bikes

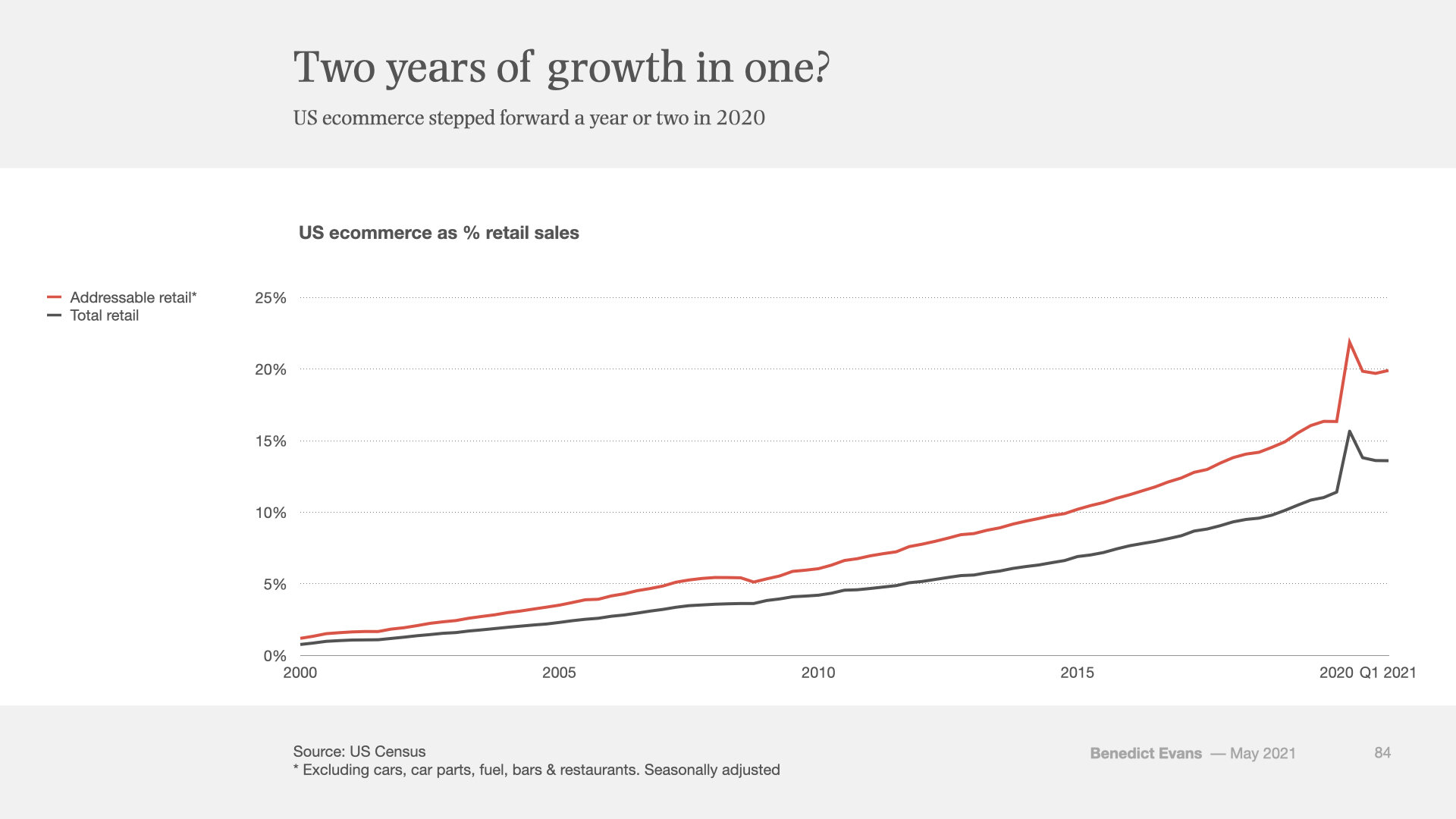

The traditional way to think about ecommerce penetration is to look at share of total retail sales, and then deduct things like car repair, gasoline and restaurants - to get to ‘addressable retail’. On that basis, US ecommerce was at 16% penetration at the end of 2019 and increased to 20% or so in 2020, adding 12-18 months of growth in a year.

The obvious problem with this analysis is that penetration of different retail categories varies a huge amount - penetration of makeup is different to books, which is different to shoes. This reflects how different the buying journey can be for different kinds of products - we sometimes talk about ‘high touch’ versus ‘low touch’ goods. The chart hides a lot of variation.

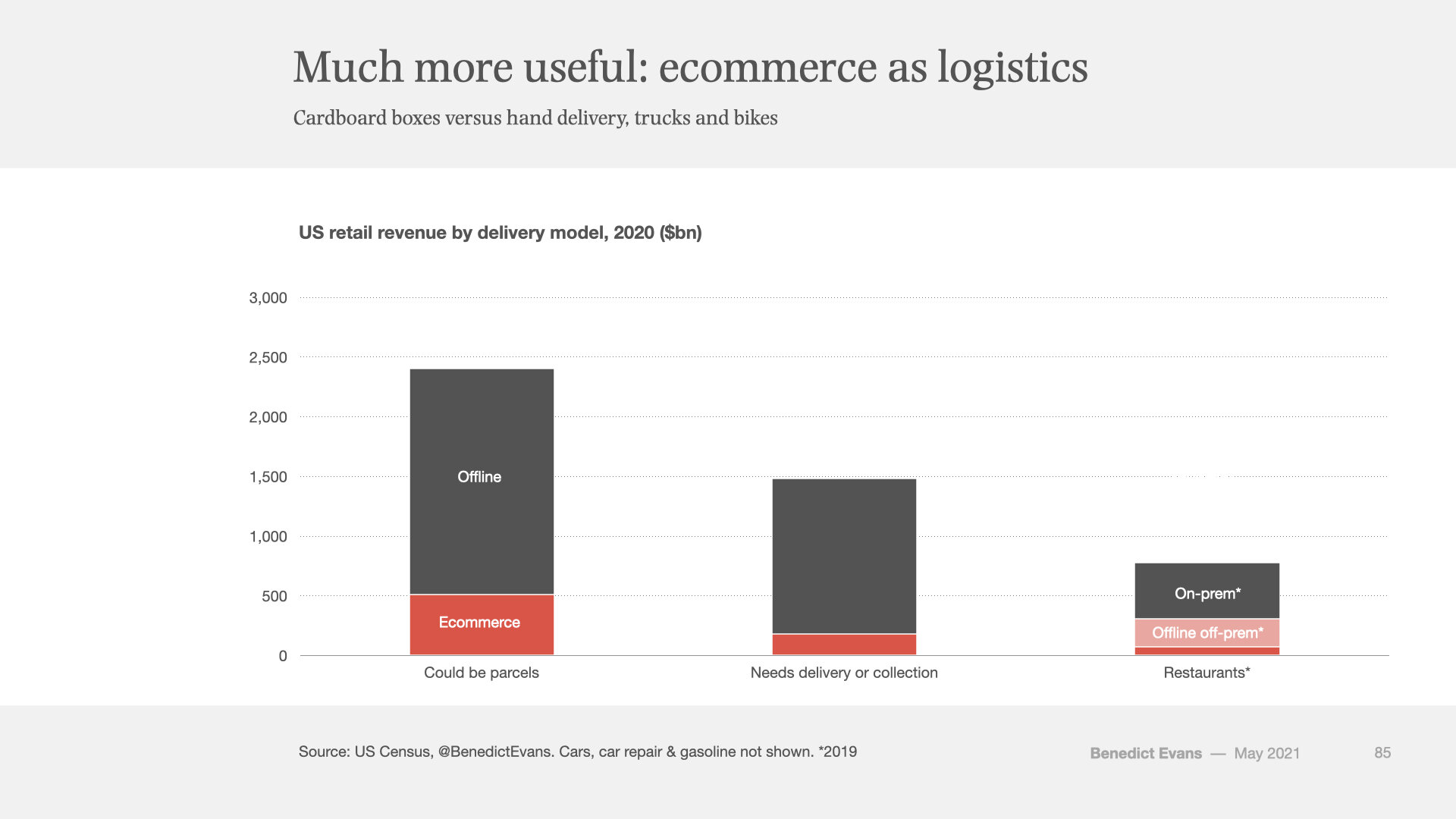

However, there’s also another way to split this, that I think is becoming increasingly important - instead of looking at the product category and the buying journey, look at the logistics model.

For Amazon, makeup, books and shoes are all just interchangeable SKUs with the same buying journey that can all be stored in the same fulfilment pod and all go into the same brown cardboard box, but a cucumber, a stove, a bag of cement or a bowl of soup do not fit this model at all - they might need a different buying journey, but they definitely need a different logistics model. So, as well as thinking in terms of hardline versus softline, or high touch versus low touch, we should also think of parcels versus collection or delivery versus bikes.

In this chart, I’ve used BLS data to put grocery, home furnishings, appliances and building and garden materials into their own category - things that need collection or some kind of custom delivery. This is obviously pretty fuzzy, and you could add and remove individual SKUs all day, but the base model for a weekly grocery shop, a fridge, or a garden project is that you go to the store, or the store brings it to you, and it doesn’t go through the mail, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be ‘ecommerce’ and doesn’t mean you can’t buy it online. You can - you just need an entirely different supply chain and delivery model, with different unit economics.

Some of the same applies to restaurants. A third to a half of US (and UK) restaurant spending was actually ’off-prem’ even before the internet - take-out and delivery is a big business, and you don’t need to believe we’ll all switch to ordering meal kits from Michelin-starred restaurants for ‘restaurant ecommerce’ to be a big thing. The internet creates new delivery models and new discovery and liquidity for this, as well as new sets of unit economics puzzles. It probably also unlocks or moves demand, and ‘cloud kitchens’ might unbundle more food from the dining room and the premium real estate, but you don’t actually have to change consumer behaviour at all for things to move around a lot. (Domino’s would say they were in the cloud kitchen business 20 years ago.) But whatever happens, it doesn’t live in a fulfilment centre and it doesn’t go through the mail.

Part of the story of e-commerce for the last 25 years has been that there is literally no category that people will not buy online, but you need to work out the right experience. Amazon has spent the last 25 year adding categories to a unified commodity shopping model and a unified commodity logistics model, but companies like Net a Porter brought all sorts of other categories online by realising you needed a different shopping model. Now we’re doing the same to the logistics side.

But if I buy online and then drive to the store to collect it, is that different to phoning and reserving it? We didn’t have a statistics category for ‘telephone ordering’. If I use an app to order pizza instead of phoning the restaurant, has that become ‘ecommerce’ or is it still pizza delivery? 30 years ago, if I drove to Walmart instead of walking to a neighbourhood store, or drove to Best Buy instead of going to a department store, we didn’t call that ‘car-based commerce’. So is this a tech question, or a retailing question, or an urbanism question?