App stores, trust and anti-trust

We all, I think, understand that the iPhone was a generational change in computing, but that change came in two parts. The multitouch interface is obvious, but the change in the software model was just as important. Apple changed how software development worked, and by doing so expanded the number of people who could comfortably, safely use a computer from a few hundred million to a few billion.

Specifically, Apple tried to solve three kinds of problem:

Putting apps in a sandbox, where they can only do things that Apple allows and cannot ask (or persuade, or trick) the user for permission to do ‘dangerous’ things, means that apps become completely safe. A horoscope app can’t break your computer, or silt it up, or run your battery down, or watch your web browser and steal your bank details.

An app store is a much better way to distribute software. Users don’t have to mess around with installers and file management to put a program onto their computer - they just press ‘Get’. If you (or your customers) were technical this didn’t seem like a problem, but for everyone else with 15 copies of the installer in their download folder, baffled at what to do next, this was a huge step forward.

Asking for a credit card to buy an app online created both a friction barrier and a safety barrier - ‘can I trust this company with my card?’ Apple added frictionless, safe payment.

All of this levelled the playing field. In the past, you knew you could trust Adobe or EA with your credit card, and you knew you could trust them not to abuse your PC too much. Panic, Rogue Amoeba or Basecamp have accumulated reputations that mean they get trust too, for tech insiders who’ve known about them for years. But what about a random Vietnamese developer who’s made a fun little game about a bird that flaps? The iOS software model removed trust as a problem, and as an advantage for big companies. You still have to hear about the app - the App Store solves distribution but not discovery - but you don’t have to worry about paying for it and you don’t have to worry what it might do to your computer.

This model has enabled an explosion of software. A billion people use iPhones today, the App Store has 500m weekly users, and those users both buy and install far more software than ever before. The new software model has, objectively, been great for software development, and also and much more importantly has been hugely and unambiguously good for actual consumers. Trust and rules are good.

The trouble is, if you have a curated, managed sandbox, where a company decides what’s safe, you have to do a good job of managing and curating, and Apple has not, always, done a good job at all.

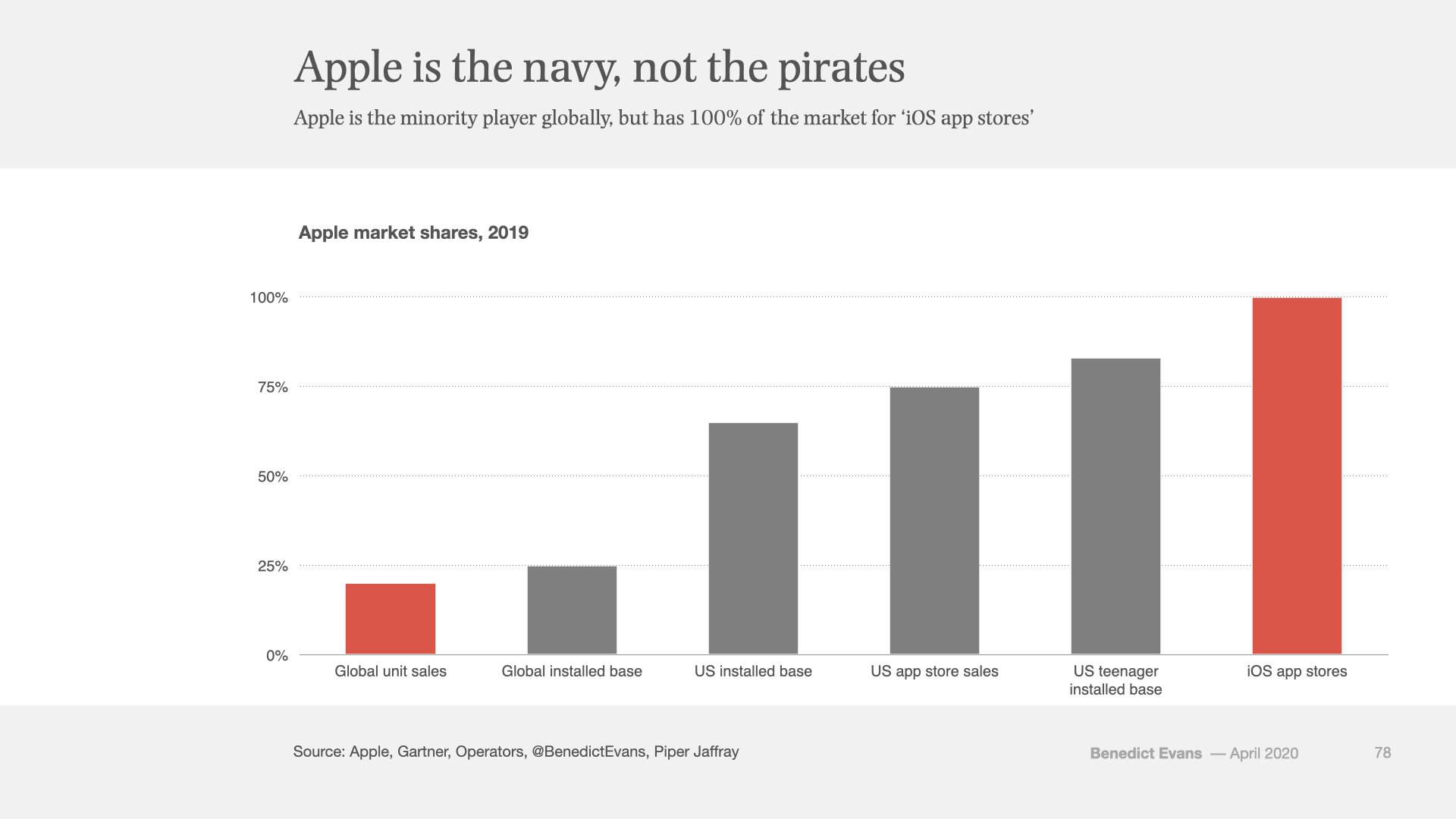

And, it matters if Apple doesn’t do a good job, because when Apple launched the app store it had sold fewer than 10m iPhones ever, but today a billion people use iPhones, and more importantly so does over half of the US market and 80% of American teenagers. For a lot of big companies, iPhone users are the market. When your product has a few points of market share you can make whatever choices you like, but when you dominate the market, other rules start applying. Apple isn’t the pirates anymore - it’s the navy, the port and the customs house. In the last few weeks, Microsoft, Google, Facebook and Epic have been stopped at customs.

So, what kinds of decision does Apple make about what you can do on an iPhone or iPad, and where are the problems? Splitting this apart:

Most decisions do actually have a solid, rational engineering basis. You can’t run in the background and record what every other app does.You can't run the battery down, or read all my photos without permission, or hijack my network connection and CPU to mine crypto.

But some seem to be just personal preference, or taste - most obviously, the decision in the last few weeks to block streaming games services from Microsoft and Google. This may partly be about revenue, but the real issue seems to be that Apple thinks that games on iOS ’should’ use native APIs, and, perhaps, that they ‘should’ work without you needing to buy a separate games controller. But whatever it is, there’s no safety, security or privacy issue - Apple just doesn’t like those apps.

Some decisions in both of two previous categories cause difficulties for third party apps that compete with Apple products. That isn’t necessarily the aim, but it also might not go un-noticed at Apple.

Then, there are endless horror stories around curation of the store. Apps are rejected in arbitrary, capricious, irrational and inconsistent ways, often for breaking completely unwritten rules. Only Apple actually knows how much this happens, but far too many people have far too many bad experiences. This has done real damage to Apple’s brand amongst developers.

And then there are the payment rules.

Apple’s payment rules, made mandatory in 2011, created a whole load of new problems:

United Airlines and Uber aren’t covered at all - only content consumed on the device is affected.

There are apps where there’s a clear logic for Apple’s payment system to be compulsory - there are coherent, consistent reasons why that random horoscope app should use the build-in payment and not be allowed to offer extra value if you give it a card, and a level playing field means the same rules for everyone (except we just discovered that Amazon is 'only' paying 15% for some Prime Video signups on iOS).

However, there’s a huge grey area around services that are consumed both on and off the platform - for example, Netflix, Disney and newspapers and magazines. How and where, exactly, should Apple get a cut?

Worse, there are companies that just can’t pay. Ebooks or music apps have to give a fixed percentage of their top line to rights-holders and don’t have a 30% margin to give Apple.

We had all these arguments in 2011 and very little has changed since: I wrote this report at the time and it’s still a pretty good summary.

Meanwhile, none of this is a surprise to Apple. As part of the recent US congress competition hearings, we saw an email from early 2011 in which Steve Jobs explicitly accepted and embraced the fact that the payment rules would be a fundamental problem for some companies. The result, for almost a decade, has been a horrible muddle, with people using those products forced into a bad user experience.

(Of course, when this email was written, Apple was still a fair way away from market dominance: there were only 150-160m iOS devices in use, and iPhones were maybe 10% of all the mobile phones being used in the USA, where today they’re over 50%.)

Ironically, Epic is not in this ‘can’t pay’ category at all, and it built a huge and very profitable business following Apple’s rules. Unlike Spotify, it doesn’t have marginal cost for in-app purchases and there’s no structural reason why it can’t pay Apple (or indeed Google). It just doesn’t want to, or wants to pay less than 30%. Indeed, one could point out that the real issue is that Epic just doesn’t ’like’ Apple’s model, just as Apple doesn’t ‘like’ Stadia.

At this point, many people suggest that we can cut a Gordian knot here - that we can slash through the complexity by letting people have a choice. Allow any payment service, perhaps in parallel to Apple’s; allow third-party app stores; allow side-loading of apps; and of course let users turn off the sandboxed restrictions on the phone. Then you can have the security if you want it, or the freedom.

Unfortunately, you can’t have your cake and eat it. A secure system with a switch to turn off the security might work for Linux and a highly technical user, but when you’ve given smartphones to a few billion people, a secure system with a switch to turn off the security is just a target for malware. That horoscope app can tell you’ll get more accurate results if it has access to some computer gibberish, so please press OK, and guess what? Everyone will press OK. A computer should not ask a question that the user won’t understand, and when you have billions of users the list of those questions looks different. This has been Google’s experience with Android: it chose a less restrictive sandbox than iOS and had many more malware problems, and Google has spent the last decade slowly rowing towards Apple’s approach.

A limited version of this argument, incidentally, is that all the problems are with the store, and you could get rid of it without security problems, relying on software sandboxing on the phones to handle all security and safety issues. But there are also policies people object to on the phone itself (no replacing the default Maps app, say), and policies that we want to keep that are enforced in the store rather than on the phone (no ads in apps for kids, say). You have to tackle the whole policy question, not just part of it, and you cannot rely on the sandbox on the phone to solve all safety and security attacks.

All of this is to say that the demands Epic makes in its lawsuit are not, in fact, merely arguing that the smartphone apps market should be more competitive, with more payment options. The sandboxed app store model is not some curious, incidental feature of modern smartphones - rather, this is an essential and hugely important part of why they have such a strong software ecosystem. Epic is explicitly arguing that we should abandon the smartphone software model and security model almost entirely, and switch to what would actually be the old Windows model. Its arguments would also of course mean that we should abandon any level playing field, and move to a model where big companies and big brands have an even bigger advantage, because a trusted platform is replaced by a trusted reputation. This would be good for big established brands - like Epic - but not for may other people.

Epic's proposal is full of holes, and Epic’s problem is really pretty peripheral, but I’m much more interested in Spotify and Stadia, where the situation now looks unsustainable, and that’s where we’re more likely to see changes. So, I think we should try to draw one more set of distinctions.

First, the App Store moderation problems are infuriating but they’re not rent-seeking or necessarily market abuse - they’re an execution failure, and indeed we’ve been here before. However, the EU, which is becoming the tech regulator by default, is already working on plans for the store review model to be regulated, with real, external rights of appeal and review, and external transparency. Apple could try to get ahead of this, or it might be too late. It might have no choice but to allow Stadia, and ‘we just don’t like that’ won’t do anymore.

Second, I think Apple is going to have to make fundamental changes to the payment model. Epic only has margin at stake, but Spotify can’t pay at all, it’s a direct competitor, and there’s no user benefit at all to Apple’s policy, just confusion and annoyance. The EU is now pursuing two separate competition policy cases against Apple: one over the App Store, with Spotify a complainant, and the other over Apple Wallet and Apple Pay. This second one is instructive: the EU is taking the view that Apple has a monopoly of payment on the iPhone. Market definition is everything. I-am-not-a-lawyer, but I don’t see how Apple can win on Spotify (or Kindle), and I don’t think it should.

That might mean changes in who and what is covered by payment rules, but it probably also means changes to the 30%. There’s a lot of argument about principle, but there’s also a price: if the rate was, say, 10%, I’m not sure that we would be having the same conversation, and Epic would certainly get less sympathy.

That 30% adds up to real money, incidentally. When the store launched, Steve Jobs said it was aiming to break even - the 30% was to cover the running costs, and it is worth remembering how many huge companies are getting the App Store, the manual review and the file downloads to hundreds of millions of users for nothing more than their $100 a year developer subscription. But the App Store is not running at break even anymore: in 2019 it made somewhere between $10bn and $15bn of commission - 20-30% of the ‘service revenue’ Apple likes to talk about.

Finally - we’ve been arguing about this since the store launched in 2008, but really, some of this debate is as old as personal computers. Right back to the 1970s, there’s been a religious split between people who want computers that they’re free to change however they like, and people who want computers that are easy and safe to use for as many people as possible. This is a trade-off, but there's a certain kind of person in tech that thinks app stores and the iOS sandbox have nothing to do with the success of smartphones and the iPhone - they're just a stupid Apple thing you could get rid of with no ill effects. 30 years ago they thought the same about GUIs, and indeed a lot of Epic’s PR comes straight out of furious Usenet posts from the 1990s about how GUIs are evil and infantilising. But the whole direction of computing since the Apple 1 has been about more abstraction, less access to the lower levels of the system and inherent in that more accessibility for more people.

Apple has always been at one, extreme, end of that debate, taking a strong opinion on how it thought a good computer ‘should’ work and letting you choose it or not. From 1976 to, say, 2015 or so, it was just one fairly niche vendor, and some people chose Apple’s opinion and some didn’t. But with the iPhone, Apple finally won the argument with users’ wallets, and that means it’s not niche anymore - Apple has become the navy, and different rules apply.