Resetting the App Store

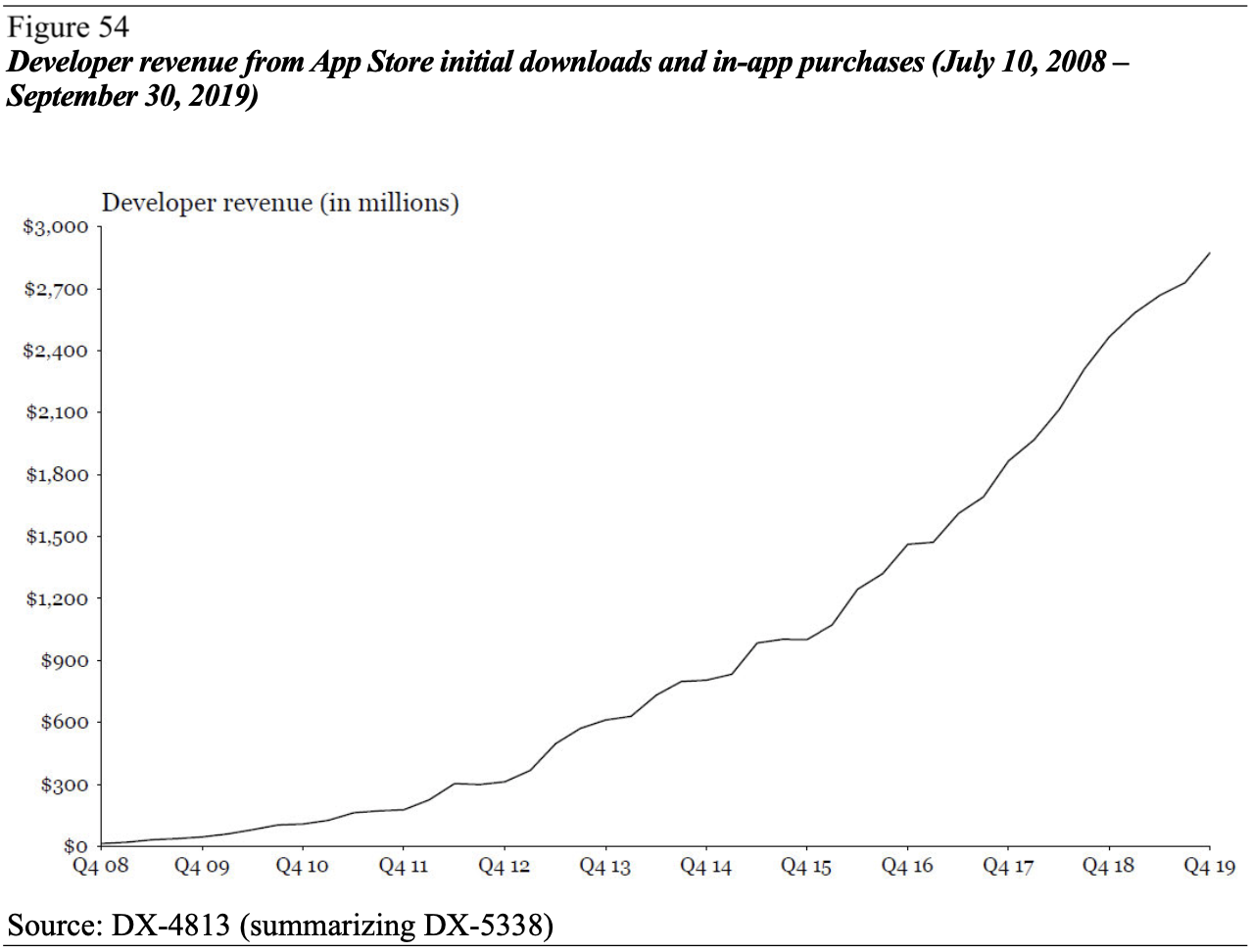

Apple launched the App Store in 2008, and tightened up the payment rules in 2011, and we’ve been arguing about it ever since. In many ways the issues haven’t really changed - it’s just that the numbers got a lot bigger.

Almost everyone understands that some kind of locked-down, sandboxed software model has been a huge step forward for both users and developers. If there’s one lesson to take from the last few years in tech, it’s that allowing any random developer to do whatever they want with your device and your data is not a good idea (and that saying they can do it if the user gives permission just creates a target). Equally, a built-in, one-tap-to-install app store with frictionless payment led to an explosion of software creation and developer revenue. Trust was a huge problem, distribution was a huge problem, and Apple solved both.*

The trouble is, if you’re going to have rules for what apps can do, what rules? And if you’re going to curate a store, how do you curate it?

Many of Apple’s decisions around this have to balance privacy, security, reliability, battery life, simplicity, ease of use, and competition. But its choices often seem to treat ‘things Apple likes’ as the most important criteria, and often seem to rank competition last. This is a particular problem for in-app payment, where Apple’s rules make some kinds of business simply ‘prohibitive’ - most obviously ebooks and music. You can be in the store, but you can’t use Apple’s payment system, and yet you can’t use your own either.

Meanwhile, there are far too many horror stories from developers of arbitrary, capricious and simply mistaken decisions in the review process for the App Store. Regardless of its actual policies, Apple makes lots of mistakes, and allows in lots of scams. Of course, only Apple know how much this happens, and at the scale of tens of thousands of reviews per day there will always be mistakes, but a lot of loyal Apple developers are unhappy.

As is often the case with complex problems, this all began with some very simple principles: “we won’t allow bad apps, we won’t let apps do things that compromise the device, and if you sell content on our platform you have to pay.” But once a few hundred thousand developers started asking what that actually meant, it turned out not to be simple at all (people working in content moderation will have pattern recognition here). My own first question, back in 2011, was that Bloomberg’s iPhone app connects to a professional subscription service that costs $2,000 a month - was Apple really asking for 30%? “Ah. We didn’t think of that.”

After a decade of this, Apple’s App Store rules have become a vast inverted pyramid of weird edge cases, exceptions and rent-seeking. Why is it OK for Roblox to have a game store, but not Stadia? Why it is any safer to give your credit card to a random ecommerce app than a random game? These paragraphs are from the latest App Store guidelines - this kind of complexity is not good for anyone, and it’s not surprising that Apple’s own reviewers make so many mistakes.

We’ve been arguing about this for a decade, but now something is going to change, partly because of Epic’s lawsuit (which it might or might not win) but much more importantly because the EU has a whole set of competition investigations into the sandbox, the store and the payment system, and is highly unlikely to accept the status quo. When Apple launched the store in July 2008 it had only sold 6m iPhones ever, but now a billion people have one, and competition laws apply, whether you like it or not. Epic might lose, but Spotify will win.

What will that mean, though? What rules will change, and how, and what will that mean for anyone who isn’t an Apple or Spotify shareholder?

Quite a lot of people in tech suggest that the answer is to let us bypass the store. Keep the security model (mostly), but allow third party stores and allow people to ‘side-load’ apps onto the phone directly. This is a red herring, for two reasons:

Half of the rules that have competitive implications happen in the sandbox on the phone, not in the store. Snap would like the option to be the default camera app, and Square would like access to NFC, and to be the default wallet. Side-loading and third party stores don’t change that.

Apple’s store is the default, and it’s a much better route to market. Making Spotify’s users jump though hoops to get the app instead of just tapping ‘Get’ in the store that everyone already uses is just as much of a competitive problem as banning it from using its own payment tool.

So, regulatory intervention might look at side-loading and third party stores, but the focus has to be on Apple’s default store and Apple’s rules. I think it’s extremely likely that apps will be able to use their own payment systems, that Apple’s 30% will change, if not necessarily disappear, and that Apple will have to give third party apps the same kinds of hardware and integration access as its own services.

That leads to a lot of very fiddly product questions. What exactly is the UI to change the default camera app? How easy is it to find? What happens when the EU or DoJ start trying to redesign those screens (and they will)? Is Apple only forced to let apps ask for a credit card, or does it also have to open up its integrated frictionless payment system to third party providers? What would the regulator say if Apple allowed apps to use Apple Pay at 3% instead of iTunes at 30%? What if Stripe could be the default in-app payment provider for every app on your phone, replacing iTunes, or could compete with Apple Pay on websites in Safari? What if other hardware had access to the same no-touch configuration as AirPods or AirTags? These are complex decisions that trade off privacy, ease of use and competition, and they might be made by lawyers.

Back to the higher-level question, though - who cares? Where is the money, where might it go and what new things might become possible? The cynical view might be that this is ultimately just a big wealth transfer from Apple to a pretty small number of big companies - mostly, games companies.

Apple collected perhaps $15bn in App Store commissions last year (and, incidentally, close to $10bn from Google for making the default search provider in Safari). 90% of that was games, so depending on where all the moving parts settle, that’s $10bn or more that would be transferred to EA, Epic and Tencent - quite a lot of which might go straight out of the door to app install ads, including to Apple. (The really cynical view would be that this is why Apple turned off IDFA.)

$10-15bn is real money, even for Apple, but it’s much more interesting to ask what else might change. There’s a small number of businesses where Apple’s payment rules were prohibitive, in Steve’s words, or at least made things very difficult - most obviously, ebooks and music. What other businesses do use Apple’s payment but would be fundamentally different if they had that extra margin? And what never happened at all? What products could not be built because of the ways that Apple’s sandbox works, that now might change? How significant are the changes in payment models I suggested above?

One could say that this is the classic unanswerable counter-factual - we don’t know what doesn’t exist. But a partial answer is to look at Google’s Android, which has always been run with much looser controls. Name ten really big, important, widely used Android apps that don’t exist on iOS. The obvious one is Chrome (there is an iOS Chrome app but it has to use Apple’ webkit rendering engine), but what else? No, not something that you use, but something with hundreds of millions of users - that’s what scale means in consumer tech today.

Of course, we can’t actually know any of this yet. But it’s possible to believe that the sandboxed App Store model has been a hugely good thing, and also that Apple has too often made the wrong decisions in running it, and also that unwinding those decisions while preserving the underlying model won’t actually change much for many companies or consumers, and won’t really be a significant structural change in how tech works. Either way, after a decade of arguing, the EU is now going to run the experiment.

* It didn’t solve discovery, but that’s a whole other conversation